Jon Pareles

BETHEL, N.Y. -- The mantra of real estate -- "location, location, location" -- was at the heart of "A Day in the Garden," the three-day rock festival that started here on Friday. The site is a gently sloping hillside that was Max Yasgur's alfalfa field and then, more famously, the amphitheater for the 1969 Woodstock festival. Two major songwriters who rarely perform, Joni Mitchell and Pete Townshend, headlined Saturday's concert.

Lou Reed, who also performed on Saturday, said backstage that he wasn't haunted by "the ghost of Woodstock." But most performers on Friday and Saturday, including some who appeared at the 1969 festival, measured the distance between then and now: between idealism and disillusionment, between bravado and practicality, between youth and middle age.

On Saturday, Ms. Mitchell sang "Woodstock," about the festival she never saw, as an elegy for a vanished moment. Introducing the song, she said, "My generation, which was given a pocket of liberty like no other generation in a century, did some of the right things for a short time."

The festival site has not been used for commercial events since 1969. Woodstock '94 took place in Saugerties, N.Y., and was presented by Woodstock Ventures, which owns the Woodstock trademark but not the site. Alan Gerry, a cable-television billionaire, bought 2,000 acres here in 1997, including the hillside; "A Day in the Garden" was produced by his Gerry Foundation.

After 1969, visiting Yasgur's farm became a pilgrimage for people who wanted to commemorate the Woodstock legend of cooperation, idealism and communal pleasure. Melanie, who performed on Saturday, has been back each year, singing for the tens or hundreds of people who have shown up on the festival's anniversaries. "I left a piece of me in this field," she said from the stage.

With "A Day in the Garden," the site of the unintentionally free festival of 1969 unveiled its new commercial role as the center of a projected theme park devoted to American music. It's surrounded by split-rail fences now, and the festival setup included souvenir stands, effective security and a magnificently clear sound system. A second stage, over the crest of the hill, presented local bands.

The festival sold 12,000 tickets for Friday, 18,000 for Saturday and more than 25,000 for today. Even with the addition of children (admitted free), daily attendance was less than one-tenth the size of the crowds at Woodstock in 1969 or at Woodstock '94. And where Woodstock was a youth gathering, "A Day in the Garden" started with two days aimed at baby-boomers now in their 40's and 50's. Today had a schedule of seven younger bands, including Joan Osborne, Third Eye Blind and the Goo Goo Dolls, and lower ticket prices; that's when the moshing started.

For the festival, concertgoers hauled out the tie-dyed shirts and peace-symbol jewelry. And nostalgia was the rule as Don Henley, Stevie Nicks and Ten Years After dispensed their hits on Friday. with Ziggy Marley sick, his brother Stephen Marley led the Melody Makers in songs by their father, Bob. Donovan, Melanie and Richie Havens harked back to the 1960's on Saturday. Melanie sang about community; Mr. Havens sang about freedom and compassion. Bill Perry, playing lead guitar with Mr. Havens, copied Jimi Hendrix's wrenching version of "The Star-Spangled Banner," now separated from its context, the Vietnam War.

But Ms. Mitchell only looked back briefly. The bulk of her set drew from the albums she has made since she released "Hejira" in 1976. They share a private, contemplative style that barely acknowledges pop's demands. Wispy, attenuated melodies float in arrangements without edges, built on reverberating guitar chords and liquid, shifting rhythms. She writes melodies like a jazz singer's improvisations, using flexibility and fragmentation instead of pop's repetition and hooks. One of the least abstruse songs she performed was from Billie Holiday's repertory, "Comes Love."

Ms. Mitchell's lyrics are diaristic, drifting from reflections on the news to questions about the purpose of life to updates on romance. In songs from her next album, due in September, Ms. Mitchell sang about lovers hiding the sounds of passion behind train whistles, about bringing a new partner home to a disapproving mother and about how "lawyers and loan sharks are laying America to waste." Even when her opinions grow cranky, what holds the songs together is Ms. Mitchell's voice, pearly and assured, making her free-floating vagaries sound like shared confidences.

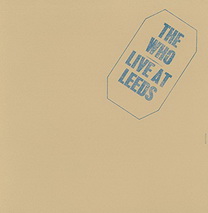

In his set, Mr. Townshend looked over his shoulder at the 1969 festival. He played two songs popularized by Canned Heat, who performed at Woodstock in 1969, and for his finale he played the same song the Who concluded with in 1969: "Listening to You," from "Tommy," this time joined by a gospel choir.

Backstage, he admitted that the Who had prolonged their 1969 set to play at sunrise; this year, he stretched songs with long vamps that shifted from meditation to filler, apparently to end past sunset.

His set ambled through his long career, from mid-1960's Who songs to one from his most recent album, "Psychoderelict," which, he cheerfully noted, was a "complete commercial bomb." Songs from his solo career were about a search for love, including divine love; songs from the Who, including radically rearranged versions of "The Kids Are Alright" and "Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere," were about youthful energy, and Mr. Townshend made them explode when he finally started playing windmill power chords on electric guitar.

Mr. Reed, whose 1960's band, the Velvet Underground, wasn't invited to perform at Woodstock, was a magnificent sore thumb. Amid the tie-dye, he and his band wore black; amid the greenery, he sang about urban grit; amid the invocations of love, he sang about random violence and violent impulses. Mostly, however, his set was about guitar muscle: lean, wiry guitar riffs, from basic three-chord rock to a furious funk crescendo. The music was smart, bruising and elegant, with no wasted motion.

Friday's show could give a younger generation ample reason to scoff at its elders. Ms. Nicks, playing through the traditional Woodstock rainstorm, was a model of baby-boomer self-absorption. "Can we do this again?" she said after her last song. "It would be so good for me." Ms. Nicks presented herself as princess, dreamer and scorned lover; the scratchiness of her voice was once the earthy balance to her fantasies, but she now sounds mostly tattered.

Ten Years After trotted out its repertory of leering blues attached to extended, repetitive jams; in one song, Alvin Lee played the same speedy guitar lick 26 times in a row. He has learned one new trick over the last three decades: tapping the strings with both hands like Eddie Van Halen.

Mr. Henley played an indifferent, professional set that reproduced the album versions of his hits, down to the guitar solos; rather than introduce any new songs, he sang material by John Hiatt, Leonard Cohen and Randy Newman. But as the Woodstock site took its first steps toward becoming a theme park, he did have a song for the occasion: "The End of the Innocence."