Heather Timmons

HERTFORDSHIRE, England, June 8 — Jerry Garcia must be spinning in his grave.

This week, on spacious lawns surrounding a turreted, gargoyle-encrusted mansion north of London, thousands of hedge fund managers and the bankers and lawyers who love them gathered for their own alternative festival, called Hedgestock.

Billed as a gathering place for the misunderstood, sometimes unloved but highly successful facet of the finance industry, Hedgestock aimed to marry the ideals, music and fashion of the 1960's with a networking event for the hedge fund world.

Or, as attendees from DKR Capital advertised during the event, "Peace, Love and Higher Returns."

The grounds of Knebworth House were strewn with a painted Volkswagen bus and clean-cut guys wearing strings of love beads, floppy hats, tie-dyed shirts and bell-bottom jeans.

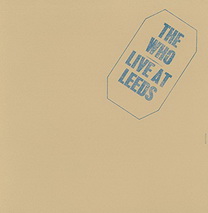

The Who, who played at Woodstock, headlined Hedgestock, and the band's guitarist, Pete Townshend, now 61 years old, did, in fact, do his trademark windmill guitar moves.

"Ringo Starr's son was the drummer, and he was fantastic," Jeremy Polturak, with Solent Capital, said.

There was little evidence that hedge fund attendees were ingesting anything stronger than Moët & Chandon champagne, which had taken out a booth.

The watch maker Breitling and the luxury car manufacturer Bentley shared a display.

Of course, there were more than a few nods to the money-making aspect of the whole industry. In addition to the Who, there were bands with names like HedgeStone and Red Herring, some with hedge fund manager musicians.

A cricket match pitted the Hunters (for hedge fund managers) against the Scavengers (for the industries that service them). There were awards in categories like "best execution O.T.C. derivatives" and "best compliance consultant."

Merrill Lynch, undoubtedly bullish on the whole idea, had brought an inflatable bull that was highly unstable and hard to ride, perhaps a nod to how difficult it is to harness unpredictable markets.

In the same vein, Michael Romanek, the director of alternative investments for Fortis Merchant Banking, arrived at Hedgestock by diving out of a plane, though naturally he was wearing a parachute.

Perhaps, despite the incongruity, the event makes sense on some levels.

Unlike the perfectly polished, traditionally dressed and generally suave investment bankers who top the food chain in big banks, hedge fund managers have carved out a niche as the finance industry's iconoclasts. They do yoga; they buy modern art; they're often socially awkward.

But if they're good, they're also often wealthy. According to Alpha, a magazine that covers the industry, the 26 top hedge fund managers took home $130 million or more each in 2005.

They have also turned charitable donations into a competitive sport and Hedgestock was no exception. All the proceeds from the £500 ($930) entry fee went to a charity for teenage cancer victims, for an expected total after expenses of more than £500,000 ($930,000).

Beneath all the costumes and the music, though, Hedgestock really was a massive speed-dating session for hedge funds. The big banks that have hedge fund clients, including Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse and Bear Stearns, laid out bars and couches for meetings, including those with institutional investors who want to expand their hedge fund portfolios.

Hedgestock attendees clutching electronic tracking devices called Spotme's, which look a bit like horizontal BlackBerries, wandered across the lawns and through tents, waiting for the beep that told them their next appointment was nearby.

Sparsely attended discussions about the industry carried an upbeat messages. "In the hedge fund environment, demand way outstrips supply," said Budge Collins, of Collins Bay Island Securities. "We won't see any softness of fees." Still, isn't there something just a little cringe-worthy about a bunch of incredibly wealthy people appropriating the trappings of a generation whose values were nearly the opposite?

When the question was posed to hedge fund managers attending the event, they had two words: lighten up.

"That's the funny part," said Ted A. Parkhill, vice president with John W. Henry in Boca Raton, Fla.

But Jonathan Watson, who teaches a class called "The U.S.A. in the 1960's" at the University of Sussex in England, said, "It does seem crass to use an association to an event that espoused peace and love" as a gathering for making money

On the other hand, he added, "it is worth noting that the organizers of Woodstock made a great deal of money out of selling the movie rights."