Penny Wark

Hedge fund managers are the new Masters of the Universe. So what are they really like? Very clever, very rich - and really very dull

It has to be said that Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey are doing their best. Townshend is pogoing like a three-year-old in need of Ritalin and Daltrey is hurling his microphone into improbable arcs and catching it every time. And the audience? Are they moving in a demonic frenzy, a look of blissed-out rapture on their sweaty faces as they yell every word of every familiar song? Er, no.

So they’re not rocking, even though they are watching The Who’s first concert since Live Aid? Afraid not. Aren’t they a little bit excited to be in a field on a summer’s evening at Knebworth, fabled home of so many classic rock concerts? If they are, you wouldn’t know. I’ve seen more passion on a Friday night in Waitrose. It’s true that after an hour of Townshend and Daltrey stoking them up with classics such as My Generation, the people near the front started to clap. "Have you lot been drinking all day?" asks Daltrey, with delicious irony.

Some of them are moving their neat hips from side to side. Click, click, just like that. But, frankly, if it wasn’t for the stage and the jolly garlands draped over expensive shirts, you might imagine you’re at a convention for City folk.

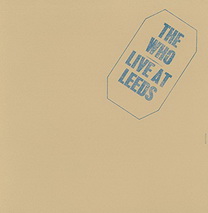

Welcome to Hedgestock. You may remember Woodstock — three days of peace, love and music back in the days when hippies were cool and half a million people swarmed into a field at a dairy farm in Bethel, New York. It was the self-indulgent summer of ’69 when everything was free, nothing naughty was off limits and no one, least of all the hippies, was counting the cost of anything. The Who were there, of course they were.

Fast-forward 37 years and Townshend and Daltrey are in remarkably good nick considering, but now they are playing to a sober crowd of hedge fund managers and their associates at an event designed to loosen them up, break down their reserve, help them to get to know each other.

As the brochure puts it wittily, this is "two days of peace and love", which is perhaps why most of them have undone a shirt button and bought a beer. One man, dressed with the icy cool of Jay Gatsby, is sitting on a deckchair, daringly licking an ice-cream cone, his laptop at his feet. Everyone still has their mobile phone on and even Daltrey’s belting lyrics don’t stop them taking calls. Eventually Townshend loses it. "Turn yer mobiles off!" he yells. There is no noticeable response.

"As an industry we have to face it, we’re not particularly loved," the brochure continues. "The establishment misunderstand us. Corporates think we’re promiscuous. Regulators wish they had the power to ground us. No wonder the Summer of Love has a certain resonance!"

I don’t know quite what this means, but then I don’t know what a hedge fund is, either, and that is part of the problem. Few outside the City understand what these people do. All we know is that they are very, very rich and that Tom Wolfe has described them as the most likely modern-day candidates to replace his 1980s Masters of the Universe from The Bonfire of the Vanities. My editor tells me that they rule the world, which makes me nervous because I am wearing my Matalan cardigan. I hope they won’t think that I’m being disrespectful.

In the car park I clock a Ferrari, a Bentley and a galaxy of Porsches, BMWs and Mercedes. So far, so predictable. A semicircle of elevated marquees and buses painted in corporate colours faces the stage, all filled with elegant people. They have glasses in their hands but they are still and distant in their manner. Perhaps they are worn out after a day of intense debate? Cheekily, JP Morgan offered a presentation called "In sourcing, Out sourcing — how saucy are you?" and someone else offered a debate "Esoterica — new risks and new returns for consulting adults".

I look around for some promiscuity and spot a couple kissing a bit near the back. But apart from the fact that they are not being promiscuous, they’re not hedge fund people, either — they are teenagers representing the Teenage Cancer Trust, the charity that will benefit from The Who’s generosity in performing for free.

How much has been raised is not yet known, though individuals could attend the two days for £500 plus VAT. Most of the money came from the sponsors and it’s a lot, everyone says confidently: "This is what it’s all about, you’ve got to put something back."

Which is jolly decent of them. But I doubt that 4,000 of the country’s brightest and most intensely competitive Type As would have gathered here just to donate to a worthy cause. In truth, this is what they call a "focused event" — they are here to network, to meet clients, to drum up more business, to make even more money. This is why their faces remain impassive, their drinks barely touched. Even the man on the baked potato stall is handing out business cards.

When a man from the Teenage Cancer Trust reads a letter from a young girl who was invited to the concert but died last week, you might expect some reaction. She had asked him not to read the letter until he was on stage, he explains, and he doesn’t know what it says. It is indeed a wrenchingly powerful letter and there is applause but no change in expression. These guys are winners, you understand, and they are here to work.

I introduce myself to a hedge fund manager called Adrian. He has a square haircut and an intensely serious manner like Ben from The Graduate. I can’t help wondering whether he needs a Mrs Robinson to show him how to relax. What does a hedge fund manager do, I ask, but he replies in City jargon that I can’t decipher. He is 28, I learn, and has had his Porsche for years.

What else does he do for fun? "Golf, some shooting, drive a car on the track."

Of course, competitive stuff. That’s why this event is also full of polo, cricket, clay pigeon shooting and even table football, so as the hedge fund managers regrouped yesterday morning it was networking that seemed uppermost in their minds. Someone had found time to buy a Bentley, "the answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind" was blasting through the speakers and some of the delegates were still wearing their jeans and daring shirts, but the faces remained closed and remote.

I find myself taken into a marquee, where two smooth and impenetrable gentlemen explain patiently that hedge fund managers operate by taking advantage of falling markets as well as those that rise. It sounds like gambling to me, but even I know not to use that word here. Typical profits, they explain, are a 2 per cent management fee plus a 20 per cent performance fee on the return. The minimum investment is around £100,000, the maximum billions, and most investors are institutions. Pounds or dollars? "Either way it’s a lot of money."

Thirty to 40 per cent of the funds fail, they say, "but you don’t hear about that. This business attracts people who want to work outside the restrictions that apply to banking."

Mavericks? The shutters have come down again. "There used to be. Not now."

These people — they are mainly men — remind me of the Su Doku fanatics I encountered at the world championships in Italy a couple of months ago: perfect corporate manners, absolute control and too serious to engage. Driven, yes. Fiercely intelligent, certainly. Though when you focus all that intelligence on one abstract area, it can make a person seem to lack empathy.

At Knebworth I meet two exceptions. The first is a hedge fund manager who kindly explains that he can’t talk on the record because he’ll be killed — professionally, he means. But the reason why his industry is so closed and so often accused of being secretive is that they have to work according to strict regulations and cannot be seen to solicit business. So they can attend a convention full of prospective clients because these people are accredited investors, but putting their wares on the table for a Times feature writer is out.

The second is Len Gayler, managing director of Cayenne Asset Management Limited, whom I have spotted bounding around to the Who — he is one of very few in the audience who actually rock, possibly because at 54 he remembers the music.

"The motto of these people is work hard, play harder," he maintains. But then he corrects himself. "Actually it depends. Some of them play hard but it’s the minority who spray champagne around nightclubs. Some of them are at their desks for 18 hours a day, never off the phone or the internet. But if you work under that kind of pressure for long enough you need to have a release valve. For some it is opera, and when the curtain comes down they go back to the office. People come off the night flight from New York, go to the office in London, clothes are delivered, they do eight hours and then go to Tokyo.

"It’s capitalism at its best because those who start up hedge funds have the chance to make money out of their own blood, sweat and tears, and being clever and using their brains. They are creative but most of all they have the drive to succeed. It’s not about the money. We want to win."

Gayler’s release valves are fast cars, going to rock concerts and raising money for the Teenage Cancer Trust of which he is a patron. Have I been to a teenage cancer ward, he asks. I haven’t. "It fills me up," he says. "We are really lucky and that’s what this is about." His eyes are watering: at last, a hedge fund manager who is a human being. Respect, Mr Gayler. Respect.