Chris McEvoy, NRO managing editor

It's the elder rocker's quandary. You're 50 years old, you look like 60, at times you feel like 80 - but you remember so well what it was like to be 26, on stage, and owning the world. So you go on stage again, risking every warning you and your peers ever made against rocking as an "old-timer."

This was the warning of Neil Young when he wrote the immortal line "Better to burn out, than to fade away." Pete Townshend said it nearly as well for his first anthem, "My Generation," when he wrote: "Hope I die before I get old."

This summer, a privileged few are very glad Townshend didn't take his own advice.

Last week, at the PNC Bank Arts Center in New Jersey, guitarist Pete Townshend and the rest of The Who took the stage in one of the first few engagements of the band's summer tour. Prior to the concert, many crowding into the open-air venue were asking the same questions: "I wonder which Who is showing up tonight?" "Will they have an orchestra?" "Is Townshend only gonna play acoustic?"

You can remove the proper nouns and insert your own time-tested band and musician. The questions may still sound appropriate. They all center on what happens to a pop-music act as it ages. The average age of the founding Who member is 56. How many crutches would they need to pull off a decent performance?

In Holmdel, New Jersey, The Who didn't need any. They came on stage as a five-some - three originals in Townshend, bassist John Entwistle, and vocalist Roger Daltrey. The young Zack Starkey (34) nailed the original Keith Moon on drums, and road-warrior John "Rabbit" Bundrick managed keyboards.

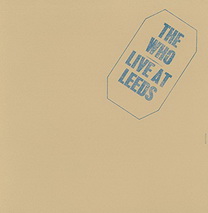

The song selection, for The Who purist, was all meat. The classics "I Can't Explain," "Substitute," and "Anyway Anyhow Anywhere" launched a set that touched every major album in the band's repertoire since the 1960s.

Technically, each band member was an accomplished master. Fronting The Who, Roger Daltrey, at 56 years old, more than adequately pulled off his usual bare-chested bravado. His vocal assignments, courtesy of Townshend, have always been demanding. In "Baba O'Riley," he achieved each high note (there are many). In "Won't Get Fooled Again," he successfully thundered rock's original primal scream.

Thanks to the big screens that now hang in most concert venues, John Entwistle's slappy bass playing could be studied - again, without conclusion. If you don't play the instrument, it's hard to comprehend how the raking fingers of his right hand coordinate with the slapping ones of his left. If you play the instrument, you may have the same dilemma. Entwistle is in another class. Following the classic "5:15," in which Entwistle constructed a long bass solo, even Townshend had to pause in amazement. "The Ox," as the staid Entwistle is known, had just soloed through two key changes, Townshend noted. "Amazing."

The same could be said of Townshend. He has always been an accomplished guitarist. And some daring fans have argued that he's better than Jimmy Page or Eric Clapton. But he's not. And he'll probably admit that. But "better" is a hard word to use when judging guitarists. Rhythmically - judging the right hand - there are few, if any, better than Townshend in the rock world. As for his left hand, Townshend has matured, and entered new territory. That night in south New Jersey, he climbed the neck of his Fender with an arsenal of broken chords, reaching a point where a new Townshend appeared. With his hammer-ons, he was Eddie-Van-Halen-like. With his blues riffs, he was in a class with Clapton.

Then, the power chord. While Townshend didn't invent it, rock historians might argue that he first popularized it. A simple chord struck loudly, and singularly, the power chord requires little more than an electric guitar and a powerful amp - unless you're Pete Townshend. For the 55-year-old rocker, a windmill strike of the right arm elevates it to art form.

The Who did everything in their youthful stage arsenal except smash their instruments. And that's good. Chances are, a few of those who drove up in their BMWs also own a Fender like the one Townshend was playing. And there may not have been a one in the audience who would have stomached its destruction.

Rock the Ages

So what allows the older rocker to reclaim the stage he was born on? Using The Who as an example, it must be a combination of factors - because not all aging rockers can do it.

The Who is a band that long-ago climbed the Mt. Olympus of rock, where groups including The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and Jethro Tull assembled. To say that The Who survived the years in better shape may be an understatement.

The Rolling Stones can be spotted on alternate years thrusting their cragged bodies back into the arena. Their music, not demanding, holds up. Their blues roots have allowed them to age adequately on stage, because blues ages so well. The music of B.B. King, and Muddy Waters and Azro Youngblood (to pull one deep from the archives) is the music of front porches and lazy hot days - timeless properties each. It's the key to the Stone's longevity.

Led Zeppelin still performs in pieces. Page here, Plant there. Robert Plant's voice cannot do it anymore, they say. Page can still mesmerize on guitar. But there is no coherent Led Zeppelin anymore, outside of the music.

And as for Jethro Tull, lead singer Ian Anderson is still assembling the act from time to time. He shouldn't be. While he still masters his trademark flute, his voice has gone South Yorkshire Pudding.

No doubt, the music of our favorite artists is solid and secure in our memories. For the emotionally connected, rock-&-roll - and folk and other genres - specifically lives in the memory within distinct boundaries of time. But while the music lasts for a lifetime, the stage act does not.

As rock critics all, we are living in a period of critical opportunity. Popular rock as we know it emerged in the '60s, played by kids in their late teens and twenties. Those rockers - if still alive - are now in their fifties and sixties. Rock's first generation is now senior. In recent years, we have had the chance to judge not only if the music lasts, but if the performers can last.

The Who has lasted for a combination of factors - each critical and irreplaceable. The Who's music carried into their fifth decade - but so did their musical ability. And their act, while electric, was forgiving and appropriate. Pete wore a bowling shirt. Roger, as mentioned above, is still allowed a bare torso. In every way, they were themselves - at fifty. Breaking between songs, Townshend told the crowd that they had recently been asked to "Be The Who" - and they did just that.

Long Live Rock

Whether today's contemporary rockers will exhibit such staying power is uncertain. Aging popular rock acts like U2, REM, and Pearl Jam (yes, they're getting older) certainly might.

Using a solid stage act as a criteria for longevity, there is a good case for Metallica to go the distance. Pound-for-pound, the group has some of the most exceptional musical talent ever assembled in rock. However, a well-aged, head-banging audience is still untested. Can the 60-year-old head hold up? We'll have to wait and see. But one can imagine the headline during the fifth Metallica world reunion tour: "Seniors Head Bowl Following Concert Tragedy."

And will the music last?

The connection between Pearl Jam lead singer Eddie Vedder and The Who's Townshend is important. Separated by more than 20 years in age they are fast friends. Pearl Jam plays Who songs at its concerts. Vedder is a studied Who fan, and while Pearl Jam's music stands well apart from The Who, there is a kinship in the depth of lyrics and sound. In a way, from Townshend to Vedder there is a handing off of the baton; anthem rock - large-intentioned popular music with a soul - now has a longer lifeline.

But it's the musician's ability that may best provide the lifeline for the live act. The Who, it must be noted, has rested on those infamous crutches in their mature years: The backup orchestra, extra guitarists, Townshend sadly on acoustic (which is conversely a joy when he plays solo).

But on July 1, in New Jersey, five musicians took the stage. They offered a lesson that every rock musician today should heed: If you can't play it, you're doomed - doomed at least to a short career.